Leopold Wenger's last letters from the Eastern Front, Aug. 1944-Jan. 1945

Poldi Wenger receives the Knights Cross from Generaloberst Otto Dessloch, Chief of Luftflotte 4, on 19 January, 1945, assisted by the General's adjutant. (click to enlarge)

copyright 2014 Wilhelm Wenger and Carolyn Yeager

Translated from the German by Carlos Whitlock Porter

First, an account of the fall of Sevastopol and the loss of Ukraine by the end of June 1944, assembled by Willy Wenger. The letters that follow, the last ones Leopold Wenger wrote to his family, spanned August '44 to January '45. Poldi had been in Ukraine since November 1943, relocating only slowly westward, but now his Group begins to move around, first to Poland, finally closer to Vienna.

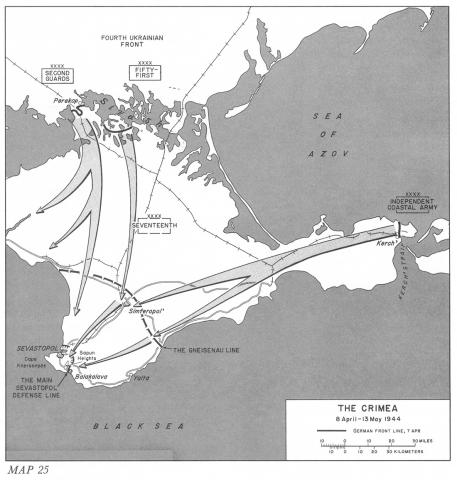

Sevastopol Falls

In six to eight weeks, the situation looked quite different. The Allies had landed in Normandy. On 5 May, the 2nd [Russian] Guard Army went on the offensive on the west side of Sevastopol. On 7 May, the [Soviet] 51st Army and Coastal Army expanded their offensives to Balaklava and conquered the crest of the Sapun mountains, with which the German commanders, two years before, had sealed the [fate of the] siege. The German commanders now abandoned their lines all the way to Inkerman, where they intended to regroup for a counterattack, after gaining the relative security of the commanding mountain heights. The situation of the defenders was desperate. One German division after the other gave way. On 8 May, General Schörner issued an order to the Navy and Luftwaffe to make the best of a bad job. On 9 May, the Soviets liberated Sevastopol. A single German unit fought a rearguard action for four days on the Kherson peninsula to permit the embarkation of survivors.

Of the 235,000 men of the 17th Army – according to the ration lists of 8 April – approximately 150,000 men were evacuated by sea to Rumania. At this point they carried only their side arms with them. Another German army had ceased to exist. A temporary calm settled over the Eastern front.

The course of the front now presented a unique spectacle. Along the northern and central section stood the German army; despite major withdrawals, still deep inside Russian territory. The Army Group North, now commanded by Colonel-General Lindemann, still held the Northern front. The Army Group Middle stood even further to the East. The Germans still stood 100 km west of Smolensk, as if they had never entirely given up the hope of a renewed offensive against Moscow.

The southern section of the front, however, had been very heavily driven backwards. The Russians had liberated the Ukraine, pushed forward into Poland, and were only 50 km away from Brest-Litowsk. They had reached the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains. They had overwhelmed Dniester and Pruth. Russian soldiers had now penetrated, not only Bukovina and Bessarabia, but even the Kingdom of Rumania. Odessa -- with Sevastopol, one of the last cities in southern Russia still held by the Germans -- was overrun on 10 April.

Sevastopol Harbor

Sevastopol Harbor

Due to the heavy fighting in the southern section of the front, the numbers and fighting strength of the German troops were steadily wearing away. Since the divisions had to defend sections of front from 25 to 50 kilometers wide, sometimes there was only one man for every 50 or 80 meters along the foremost front line. There were no reserves, and no relief.

Operations were made even more difficult by increased partisan activity, particularly in the territory of the Army Group Middle. The Soviet Union was full of partisans, everywhere the Germans went, but nowhere so numerous as in White Russia. Every night, listening posts counted between 100 and 200 airplanes, flying in supplies for the 225,000 partisans. The armies had only one supply line left, upon which the Germans concentrated their full attention, without, however, ever entirely eliminating sabotage and partisan attacks. It was war without mercy, which spared neither the wounded nor prisoners, in which uncertainty was answered by terror, shrinking from neither torture nor desecration of the dead. The civilian populations were, almost without exception, bitterly hostile, although there were occasional, very willing and useful German sympathizers.

German measures intended to deal with the increasingly difficult military situation were becoming more and more ineffective. In early 1944, the first German recruits born in 1926 appeared on the Eastern front: soldiers aged 18, of whom anything could be demanded. But this arrogant faith was refuted by Russian realities on a daily basis. One third of all German troops fighting on the Eastern front had already been wounded once and nonetheless declared fit for further service. The destructiveness of the air war on Germany had a depressing effect on soldiers during their rare furloughs at home. The melancholy Russian landscape, the abandoned villages, the impression of emptiness and the uncertainty of links with the rear, as well as the extremely unreliable postal links with home, had a demoralizing effect, under which confidence turned to resignation, resignation to fatalism, and fatalism, finally, turned to despair. The German armies were aware that, basically, they had been defeated once and for all.

Replacement parts and new materiel deteriorated in quality, since raw materials like manganese, nickel, molybdenum and wolfram were no longer available in sufficient quantities. With the destruction of the Rumanian oil fields by the Americans, the monthly fuel deliveries sank to almost half that of the previous month (May1944). Units at the front could often hardly plan from one day to the next; mobile units were threatened with complete paralysis.

Hitler prohibited his generals from evacuating even one single foot of occupied territory, promising his generals a quiet summer. As in past years, the middle section was believed destined to become a secondary theater of war, in which one only need expect occasional local attacks.

It was in the southern section that the Russians could be expected to attempt to expand upon the advantages already gained during the winter months, in an effort to push through to the mouth of the Danube, driving the Germans out of the Balkans, capturing the Rumanian oil fields and threatening Vienna. The Führer had already taken measures to contain the anticipated offensive “blow for blow“, reinforcing the two army groups in the south as much as possible. The offensive was to break up against the steel core of the Wehrmacht. The Red Army was said to be a mass of unreliable stability. A singe push of sufficient violence could bring it to its knees. This was how the Czar’s armies had broken up in its offensive against Germany in 1914, in one single push; the same thing happened to Lenin’s army during its attack on Poland in 1920. The contribution of the Army Group Middle to final victory would consist of holding the front with the forces it had available.

The Army Group Middle was made up of four armies. The 2nd Army, weakened and demoralized, held no less than 500 kilometers of front east of the Pripet Swamps, but had little contact with regular Russian military units. The 9th Army stood on both sides of the Beresina. The 4th Army was attached to the 9th; it crossed the Dnieper twice before it made contact with the 3rd Army.

The month of May was already over; June had just begun. Rome was lost; there was heavy fighting in Normandy, but relative quiet reigned in the East. German reconnaissance troops, however, were becoming increasingly nervous. In the regions occupied by the Army Group North, as well as by the Army Groups North and Southern Ukraine, there were no signs of any preparation for an offensive. At the same time, the Army Group Middle reported considerable concentrations of enemy troops. The major Russian offensive, therefore, was to be played out here, instead of where the German High Command had most effectively prepared for it. It was not aimed at the Rumanian oil fields and iron ore deposits, therefore, at which Hitler stared like a man spellbound. With astonishing organizational skill, the details of which are not known to us, Stalin had succeeded in shifting the bulk of the Soviet forces 500 kilometers northwards.

The Soviet offensive against the Army Group Middle began on 20 June with a large-scale partisan attack. Partisans appeared without warning, everywhere, out of nowhere, attacking roads and rail lines, as well as supply depots, involving the Germans in 3,500 individual combat actions and causing 10,500 explosions on the railway lines.

Forty-eight hours later, at dawn on 22 June 1944, after a muggy night, interrupted by vehement summer storms, Soviet tanks and infantry units went on the offensive against the German 3rd Tank Army, attacking the 9th Army on the very next day, throwing 140 infantry divisions and forty three tank brigades into battle against the thirty-four divisions of the Army Group Middle and the sole remaining German tank division.

The summer offensive was characterized by one menacing innovation. A rolling barrage, including the massive use of Stalin organs, smashing the German front lines, was followed by a preparatory aerial bombing offensive which astonished the Germans with its violence and range. Apart from the 6th Air Fleet, which was assigned to the Army Group Middle, the Werhmacht had practically nothing with which to counter this violent offensive. The Air Fleet had only 40 usable fighter planes on 22 June. The result was an astonishing reversal of the previous conditions, reminiscent of the situation in Normandy: German soldiers in the East were now fighting an enemy in possession of absolute superiority in the air.

* * *

From this point on (summer 1944), several letters are missing. Something must have gone wrong with the postal deliveries, so a few things got lost. In any case, Poldi’s letters became fewer and farther between; he presumably had much less time to write as a result of the intensfied, exhausting combat missions. -WW

Above: August 1944, the squadron lives out in the open in tents close to where their planes are parked, in Sochazew, Poland.

Below: Poldi looks at the photographer as he and Lt. Heiermann converse while relaxing on the grass.

13 August 1944: … I finally got another letter from Dad yesterday; it took a long time getting here, since it was dated 13 July. The main thing is, that it got here at all. You’ve been in our summer house at Gleichenberg for 2 months now, and the two young ones must be enjoying it. Gretl and Gerhard are certainly better off down there than in Leoben. Even if the area did get hit by a couple of bombs, it’s not so bad, since they were probably just dumped by a plane that got shot up and had to jettison its bombs in an emergency.

Otherwise, I like to imagine being with you at this time of year. It’s just a shame that the restrictions on furlough are so strict – they’re not going to be relaxed now. It’s not particularly beautiful where I am now [according to the flight log book, Bielice, Poland -ww]. Especially, living in a barracks is really no fun at all. But it’s better than being quartered in a dump full of bedbugs with some filthy Pole.

I haven’t got a lot to say about myself. It’s all the same here. As usual, I spend most of my time in the “upper air“, I’m in good health and feel good. I got a letter from Willy (from Leoben, still), in which he tells me about his school-leaving examination:

“After approximately 8 years of stubborn fighting and bitter struggle, committing all my forces, including reserves and auxiliaries (“to hell with it”, crib sheets, etc.), I was finally able to bring about a victorious end to the fighting through a quick and decisive victory.“

When I read that, I really had to laugh. I hope he always keeps his sense of humor!

In the meantime, Poldi came home on furlough and built the veranda on our house, together with Dad.

His flight log book ends on 24 August 1944 with the entry of his 368th combat mission, out of Bielice. His very last flight book was lost at the end of the war and the following information was taken from what remains of his letters. -WW

Poldi stands in front of a German Headquarters building in Krosenow, Poland in September 1944.

14 September 1944: After a long, circuitous journey, I finally arrived at my old point of departure yesterday morning, 14 September, was reunited with my unit and flew a mission with them in the afternoon. I had to spend the whole night in Vienna [coming from Leoben -cy], then Breslau, from 17 hours to 5 in the morning, then on to Litzmannstadt [Lodz] where I spent half another night someplace from 14 hours to 21 hours. Things moved a lot faster at home. I only had an express train from Vienna to Breslau, the others were all local trains. It was really no fun.

Otherwise, things are still the same; except that a non-commissioned officer has been killed. Autumn is approaching and it’s quite a bit cooler, but there’s beautiful weather again today. My new LG.P. is Posen now! I went to the cinema twice in Litzmannsstadt, saw “Major als Herr“ and “Der Vetter von Dingsda“,

16 September 1944: You’ll be happy to hear some news from me for the first time since my arrival at my unit. I’ve been here for 4 days now – how time flies! The weather is still good and I’ve had a lot of work to do from the very first day. Of course, I only yesterday flew my first mission since I got here, but they’ve scheduled a lot more for me. Nobody wanted to have to be the one to inform the relatives of our NCO who was killed recently; so the heavy duty fell on me. And a lot of other things, too, so I spent almost two days just at a desk. But I made up for it by flying today. Flying over Warsaw, I was able to see that the city can really be described as entirely destroyed. It looks ghastly. The Soviet positions look the same as ever, but only because they’ve stepped up their air defences like you wouldn’t believe. The whole sky was full of little clouds from the bursting shells.

I’m living in a street maintenance worker’s cottage on the edge of a busy street, and since my other comrades relieved me during my furlough, they took off as soon as I got back, so I’m alone, thank God, in a nice, friendly little room, warmed by a tiled stove.

The rations have gotten better. There’s even a cinema in our little aerie—we saw two films yesterday. Only, we have no electric light. That would make it the ideal winter quarters.

When I got here – I’ve got to tell you this – there was a big celebration in the evening, with roast chicken and so on. So I got back into the old routine in no time.

13 October 1944: I’ve been back with my old unit again for two days now. There’s not a lot to do. It’s really very boring. I’m staying in an ethnic German village, quartered with a building contractor. We helped out with the wine harvest yesterday, and then at the corn husking. We didn’t fly at all. The Americans simply flew over us at higher altitudes.

Right: Poldi enjoying some bucolic interaction while quartered in an ethnic German village.

I got to Wiener Neustadt just in time, at precisely 11 hours, although the train only travelled as far as Mürz. But to Gloggnitz [in the Vienna basin] and on to Wiener Neustadt I rode a locomotive, so I got here earlier than I had dared hope. At 16 hours it travelled on further, to Fünfkirchen [in Hungary], where I stayed the night and got to the collection point the next afternoon, since it wasn’t far away. So I’m sitting here and waiting for everything to get put together; till then we can’t do anything.

I was happy to be able to speak to Dad at the railway station, although it was only for a short time.

From letters written home by myself in October 1944 from Oschatz, it appears that Poldi made it to Wiener Neustadt again in the early fall (presumably he was already stationed in Hungary) to pick up a new Fw 190. He was able to notify Dad beforehand, who hurried to Wiener Neustadt to meet him. There, he had an opportunity to admire Bibi’s new plane and even sat in the pilot’s seat. But when Bibi started the motor he jumped out as if he had been bitten by a tarantula and ran away.

Above: Leopold Wenger Sr. visits with his son in Weiner Neustadt when Poldi comes there to pick up his new Fw 190.

Below: Poldi proudly poses with his brand-new beautiful plane as Dad snaps a picture.

Right: Possibly the last picture of Poldi with his father was taken at Neustadt, in which they uncannily appear to be already communicating in the spirit dimension.

-------------------------------------------

11 November 1944: If everything goes according to plan, Gefreiter Hlavaty is going to give you a ham that’s been salted for eight days now. After another two weeks of salting, it‘s going in the smoke chamber for three days. Or it can be eaten just like ordinary meat. If Gefreiter Hlavaty is unable to travel any further (to Vienna) could he spend the night with us? He is my former wingman.

12 December 1944 (from Hungary): The weather has turned bad again, starting a few days ago. For days, you could hardly see your hand before your face. But the other side has left us alone for the same reason. The weather got better for a few hours again today and we had to watch the squadrons of 4-engine bombers flying towards Germany. When you see that, you feel like exploding with rage.

Once again, today, I participated in the machine-gun defense of our positions against low-level air attacks. Then we paid the other side a visit and showed them a couple of things. We were treated to another film yesterday. For the first time I was able to see a film and a newsreel, but which I had already seen on furlough. Anyway, it made a nice change. Otherwise, there’s nothing new to report.

17 December 1944: Did I already tell you that I was presented with four bottles of champagne by my Commander (Major Götz Baumann) on the occasion of my 400th combat flight? I’m saving them for special occasions.

Since it’s Christmas in a few days, I would like to wish you all the best in this beautiful festivity, and hope you have a few beautiful, comfortable days undisturbed by alarms of any kind. Please let me know how you passed the holy evening. To Gretl and Gerhard, I wish many beautiful hours under the Christmas tree – if everything goes well, as planned, I’ll be able to celebrate the holy evening together with the squadron.

25 December 1944: The holy evening is now over, and we were able to celebrate together with the whole squadron as usual. We fixed up a large room for the purpose and decorated it with Christmas motifs; when I got back from the landing field, everything was ready. Festivities started around 7 in the evening. After a couple of Christmas songs I rose to “address the squadron” and then the Commander appeared, right on time, at the common evening meal. There was a great deal of roast veal to gulp down and we were surprisingly well blessed with “special demand items.”

The evening’s celebrations ended with the reading of the Christmas newspaper and a speech by Dr. Goebbels, and then everyone was left to pursue his own private thoughts. For me, this Christmas holiday brought a special event. I had to do a belly-flop landing due to motor damage on my first mission before reaching the front and only got back to my unit after much hitch-hiking on trucks and changing vehicles many times.

Since two of our people are lucky enough to be leaving on furlough and will be passing through Leoben, I intend to take the opportunity to send you a couple of little things that will make you happy. You’ll find the alcohol very tasty and the leg of pork, too, especially on New Year’s Eve. I wanted to have it smoked here, but due to the uncertainty of staying anywhere in any one place long enough to have time for it, I didn’t think it advisable. The leg of pork has already lain 10 days in salt and I hope to enrich Mom’s larder somewhat with the lard. The two fellows who are going to bring it to you, are my sergeant major and my airman. Now, dear parents, I wouldn’t like to miss my opportunity to wish you all the best at this, the commencement of the beginning of the year 1945, and I hope that this year will produce the long-wished-for and much-aspired victorious conclusion to the war and peace. I would also like to extend my best wishes to my little brother and sister for the coming New Year that is about to begin.

11 January 1945: I don’t know what I’m supposed to think, as to why I have not heard anything from you. Your last letter was dated 6 December and I haven’t had anything since. What’s new at home? If my sergeant major has visited you on his way to St. Anton, as I hope he has, he’ll certainly have a lot to tell me about you when he gets back. But I’d rather hear from you personally! I can’t tell you a great deal of news about myself. I’m healthy and things are going well for me. It’s been snowing a lot for a few days now and we have a really nice winter landscape to look at. Unfortunately, it’s thawed a bit over night and the landing field is a real morass. That is less comforting.

Although the weather was not always very good, I was still able to fly a few really beautiful and successful missions. You can see from the Armed Forces reports how it’s going for us generally. Since I haven’t got anything further to say, I will say good-bye for now, hoping finally to get some news from you soon. Otherwise I’ll have to check up on you myself.

Please accept my best greetings and please write often,

Your Bibi

The letter dated 11 January 1945 is the last one that I could find. Poldi (Bibi to his family) must have written others home, but these were all lost at the end of the war. The letters that I received from my brother were lost, together with my luggage, during my transfer to the Eastern Front in Brandenburg. The following reports are therefore written from memory. -WW

Poldi is awarded the Ritterkreuz (Knights Cross)

In January 1945, towards the end of the month, I received, in Oschatz, at the LKS 3 (Air Warfare School #3), an officer cadet school where Poldi’s military career began, a letter with three photos showing him upon the occasion of his being awarded the Knight’s Cross (Ritterkreuz). This was my last message from him; I was sent to the front and had no further postal contact with either Poldi or my parents, from this time onwards.

Above: High level visitors arrive at the Squadron's quarters to give Germany's highest military decoration to Oblt. Leopold (Poldi) Wenger for his exceptional bravery and leadership, and his accomplishments. General Dessloch looks toward Poldi as the men of the squadron line up to honor their Capitan.

Below: Hauptman Götz Baumann, far left, Poldi's Group Commander, gets into the joyous spirit of the occasion. Gen. Dessloch in center.

Above: Generaloberst Dessloch listens to Poldi while Commander Baumann beams in the background.

Below: All the men of the 10 Staffel "Red Foxes" pose together in a pretty winter setting; Poldi is 5th from left in front.

After being awarded the Knight’s Cross, Poldi got a few days furlough. That must have been toward the end of January. It was his last meeting with his parents and his younger siblings Gretl and Gerhard.

On his last visit with his parents and siblings in Leoben in late January 1945, Poldi looks fit and elegant, as always.

The Soviet advance through Rumania towards Hungary was proceeding with unimaginable fury, involving the commitment of unbelievable masses of soldiers and materiel. Thousands and thousands of tanks attacked relentlessly. Their losses were horrendous, and, what was even stranger, the Russians always succeeded in throwing more and more tanks into the fray despite the high casualty rate; the attacking Russians resembled a column of ants. Bibi’s squadron was compelled to fly a correspondingly large number of missions against this rolling wave of steel. He told me that he had destroyed large numbers of enemy tanks, but almost every letter contained a description of the increasingly higher German fighter pilot casualty rates.

His stay in Hungary was especially friendly, and the food was so good that nothing could compare to it. But the Soviets overran Hungary with unimaginable rapidity, and it sometimes happened that German pilots had to take off from one end of a runway where Soviet tanks were already penetrating the other end of the same runway.

German fighter and ground attack pilots flew constant missions against very fiercely concentrated anti-aircraft fire; it was not unusual for Poldi to be compelled to describe seeing one of his wingmen being shot down, or being blown to pieces by his own bombs as a result of a direct hit in the air. He also described the constantly increasing numbers of modern Russian fighter planes, some of which were superior to German planes.

The Soviets established fortified bridgeheads which put up a stubborn defence, protected by strong flak units, all along the Danube, along with numerous pontoon bridges and large quantities of landing craft which were repeatedly attacked by German FW 190s with bombs, cannon and machine guns during the last few weeks of the war.

Poldi‘s squadron, the erstwhile Red Foxes, was now compelled to change positions repeatedly, fighting a rearguard action: from Semlin-Belgrad, Fünfkirchen, Batasek, Nagy Vaszony, and Bad Vöslau to St.Pölten/Markersdorf.

Last mission

Poldi flew his last mission from St. Pölten. According to his airman, Lt. Loidl from Bad Hofgastein, Poldi shot down several Russian planes on 4th and 5th April. According to other statements by the same pilot, Poldi went to the dentist on the morning of 10 April 1945. He then took off from the region of Gänserndorf to destroy some Soviet tanks which had broken through our lines. As his wingman, he appointed a very young pilot who had only arrived in the unit a few days before. He chose to take this inexperienced pilot under his wing to teach him attack tactics. After hitting the Soviet tanks, they were attacked over Vienna by fighter planes that had the sun behind them. Poldi flew directly at the enemy planes firing everything he had, with German anti-aircraft fire in between them. The young pilot succeeded in escaping from the enemy and landed safe and sound in St. Pölten. Poldi was listed as missing.

It was later discovered he had done a belly-flop crash landing on a railway embankment in the immediate vicinity of the old airport at Aspern and bled to death as the result of a very serious back wound. It was assumed that he had been wounded by a large grenade fragment, which may have been a result of the anti-aircraft fire. Oberleutnant Erhard Nippa, however, reports that for a long time there was talk in the squadron that he had been ambushed by FW 190s captured by the Russians and flown by Russian or Hungarian pilots.

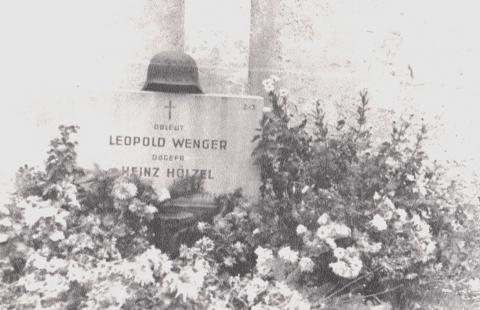

He was buried a few days later, together with an infantryman, at the local cemetery in Hirschstetten near Vienna.

Poldi's grave at the small, well-kept cemetery at Hirschstetten, near Vienna.

Oberleutnant Leopold Wenger (19 November 1921 – 10 April 1945), recipient of the German Cross in Gold and the Knights Cross (Ritterkreutz); Squadron Commander of 4/Schlachtgeschwader 10 of Jagdgeschwader 2, Luftwaffe.

Category

Austria, Germany, Leopold Wenger, World War II- Printer-friendly version

- 18553 reads

Comments

Leo Wenger

I write to thank you for posting the Leopold Wenger story which I have followed with great interest. His death so close to the wars end adds to the tragedy. He was a valiant young man typical of many who died for Germany, and reading his story has made me very proud to know of him.

Leopold's letters

Thankyou Carolyn for allowing us to see the other side of this war. Although I am English and was 16 years old in 1945, I always felt the German people were very like us. What a terrible waste of life,

Thankyou again.

Leopold Wenger

Utterly poignant! Very interesting. Still so little literature from this period of the war. A vast and little understood conflagration. My heart goes out to all who perished and suffered during this time.

Poldi's letters home

Very interesting, personal and intimate viewpoint of one persons war. From the fun optimism in France to the increasingly harrowing and costly reports from the Ostfront, the letters provide a great insight into life on a Schlachtgeschwader.

Thank you so much for publishing these letters home.

Regards,

Kevin McDonald

Thank you

My first visit to your site. Thank you and the family for sharing these personal letters of such a brave man.

Should be a book?

Thanks for commenting, Cyndy. I'm getting ready to look into publishing his letters as a book. I think they deserve it.