More revelations of Anglo-American crimes as condemnation is heaped on Germany

IN THE JANUARY 24, 1917 ISSUE OF THE FATHERLAND, which will cease publishing under that name with the February 7th issue, the unsuspecting editors are still exposing the hypocritical nature (to put it kindly) of prominent pro-British, pro-Allies spokesperson Elihu Root. This former Republican senator from New York was President Theodore Roosevelt's Secretary of War during the Philippine-American War (1899-1902) when many atrocities were carried out against the Filipinos. Knowledge of that was prevented from reaching the American public. Writer Franklin Schrader uncovered secret documents and exposed them perhaps for the first time, at least for most Americans. The second article below adds to what was revealed in my prior post on Elihu Root's conduct of the war. But first, another “crime” revealed by a Fatherland reader. -cy

vol. 5 no. 22 Jan. 3, 1917 Page 4

ENGLAND BREAKS ANOTHER PACT

ENGLAND BREAKS ANOTHER PACT

Letter to the Editor of The Fatherland

Sir:

In the issue of October 18th in an article written by Mr. C.A. Collman THE FATHERLAND drew attention to the scandalous robbery going on in Nigeria where German property, real estate, warehouses, factories, wharves, residential sites, etc., etc., are to be forcibly sold by auction.

The immorality of this transaction has been amply pointed out by Mr. Collman. It is typically English. In Europe Great Britain presents to the world the mask of angelic purity suited to her role of upholder of international law and defender of international treaties. But in Africa, where nobody gives much thought or attention to what she is doing, England pursues her old historical course. What she is doing in Nigeria is not necessitated by any vital interest. It is not an act of self-defense as was, for instance, Germany's invasion of Belgium for which England professes so much moral indignation. It is an act of wanton robbery and as such contemptible. But it is more than that, it is a direct breach of England's pledged word, one link more in the endless chain of British broken promises. It is a violation of a solemn international treaty.

There is a treaty called the Act of Berlin, a solemn covenant of some ten powers, the United States among them, signed on February 26, 1885. Its fifth chapter treats of the navigation of the river Niger and here, in Article 30, par. 4, Great Britain pledged her word as follows:

“Great Britain undertakes to protect foreign merchants of all the trading nationalities on all those portions of the Niger which are or may be under her sovereignty or protection as if they were her own subjects, provided always that such merchants conform to the rules which are or shall be made in virtue of the foregoing.”

And further in Article 33:

“The arrangements of the present Act of Navigation will remain in force in time of war.”

Thus in 1885 England promised to treat all foreign merchants even in time of war on a par with her own subjects. And in 1916 she tears up that scrap of paper and robs the German subjects of the fruit of many years of labor and industry.

What is almost worse than this act itself is her impudence in advertising the sale in the United States of America. When reading that advertisement I was at first at a loss whether it denoted the brazenness of the inured criminal or the cowardice common to thieves and which makes them crave for accomplices. I now incline to take the latter view.

That any decent American who knew what this “sale” means would bid to secure any property stolen from German subjects even England cannot assume. Her advertisement in the American papers of the sale aims to entrap the unwary; it is designed with the purpose, through the improvident action of some individual American, to entangle the United States in this dirty business so as to have us on her side when the day of reckoning comes. It is to be hoped that American investors have been too busy placing their money in decent American undertakings to even give Nigeria a thought.

At the same time it is to be deplored that, as far as I have seen, with the exception of The Fatherland, not one single newspaper or periodical in the United States has had a word of comment such as England would have deserved for her dark doings in the dark continent. KENNETH M. MARTIN Brooklyn, N. Y., Dec. 16, 1916

__________________________________

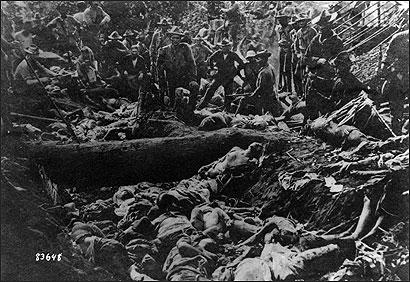

US Soldiers pose with Filipino Moro dead after the First Battle of Bud Dajo, March 7, 1906, Jolo, Philippines.

vol 5 no. 25 Jan. 24, 1917 Page 5

MORE REVELATIONS OF ROOT'S RED PAST

By Frederic Franklin Schrader

IT is important to remember that in dealing with Mr. Elihu Root, the inspiration and most eloquent mouthpiece of the Allies in the United States, we are dealing with a person possessed of one of the most subtle minds in America. It is said of a formerly great factor in financial operations who employed Root as his attorney that he used the words, “other lawyers can tell me what not to do, but Root can tell me what to do and not get caught.”

Root passed into American history with the memory of the greatest political highbinder in the dirty affairs of New York City, more than a generation ago—Boss Tweed, whose attorney he was. Tweed was sent to prison to expiate his crimes. Root rose to become Secretary of War, Secretary of State and United States Senator from New York.

It is strange that neither Root nor Roosevelt raised their voices in behalf of Belgium until shortly after the Belgian Commission came over and called on the ex-president in the autumn of 1914. In September of that year Roosevelt wrote in the Outlook: “We have not the smallest responsibility for what has befallen her (Belgium).” After the Belgians had seen him he wrote: “When Germany thus broke her promise, we broke our promise for failing at once to call her to account.”

Some strange, mysterious influence had worked on Roosevelt's mind between September, 1914, and the visit of the Belgian Commission. And it was not long after that event that Root as mysteriously reversed himself and began to denounce Germany for her invasion of Belgium. In an address made by him in the spring of 1914 as president of the American Society of International Law, he said (July number of the American Journal of International Law):

“It is well understood that the exercise of the right of self-preservation may, and frequently does, extend in its effect beyond the limits of the territorial jurisdiction of the State exercising it. The strongest example probably would be the mobilization of an army by another power immediately across the frontier. Every act done by the other power may be within its own territory. Yet the country threatened by the state of facts is justified in protecting itself by immediate war.”

What had transpired to change Root's mind between the spring of 1914 and the summer of 1915, when he first began to utter public denunciations of Germany for doing what as president of the American Society of International Law he had so lucidly justified her in doing to protect herself?

I RECENTLY showed that Mr. Root with the decrepitude of age has developed a lamentable lapse of memory as well as a remarkable facility for changing his opinion according to circumstances. He forgot that he stands accused by a committee of American citizens of supplying one of the blackest chapters in our history. In his address on the “enslavement of Belgium” at Carnegie Hall, December 15 last, he drew this picture of the German action in Belgium:

“In Roman times the standard of conduct permitted the carrying off of slaves to the mines; permitted the impaling of prisoners; permitted the sacking of towns. At the time of the Thirty Years War, outrages almost as bad as those which have been perpetrated in Belgium were in accord with the practice and acquiesence of the world; but we thought that we had been building up new standards of conduct, that the world had grown more compassionate, and more kindly—and it had. The public opinion of the world was establishing, had established, a more humane and Christian standard of conduct, both in peace and in war. That standard is now beaten down, it is destroyed, it is set at naught. And if we remain silent, if the great neutral peoples of the world remain silent, the standard is gone forever.”

There is more in this same vein, the heart-rending sobs of a paid attorney in a desperate case. What Root forgot was that he is accused of having beaten down these very standards of civilization while Secretary of War under Roosevelt. The accusation is in these words:

“Mr. Root, then, is the real defendant in the case. The responsibility for what has disgraced the American name lies at his door. He is conspicuously the person to be investigated. His standard of humanity . . . . proves that he is the last person to be charged with the duty of investigating charges which, if proved, recoil on him.”

This indictment bears the names of Moorfield Storey, Julian Codman, George Francis Adams, Carl Schurz, Edwin Burritt Smith and Herbert Welsh.

The attempt has been made to whitewash Root of his record as the destroyer of the standards of civilization; as the man who, these men said, “disgraced the American name,” and at whose door the real responsibility for the Philippine atrocities should rightfully be laid. Root had his friend Lodge in the Senate to aid him in hushing up testimony that was printed at the time in every newspaper in the land and proclaimed from every houstop by those who witnessed and participated in the atrocities. Henry Loomis Nelson wrote to the Boston Herald, July 28, 1902:

“Freedom of speech on this subject would be exceedingly dangerous. It is quite probably that when Gen. Smith comes home, there may be further talk, in which event the (war) department will endeavor to silence it; for silence on this subject is to be enforced, if possible. This inc ident in the history of our warfare in the Philippines is to be considered as closed, if those who are responsible for the war can enforce their determination on the subject. Mr. Lodge's committee will probably never resume the investigation, which therefore results in nothing; and the Republican newspapers will help him suppress the dangerous truth.”

THE committee named above tested Mr. Root's statements and explanations. In their report they printed the statements as well as sworn testimony brought out at counts martial but never permitted to reach the public through any other channel, for Root had to be saved, and to do so court proceedings were quashed and annoying witnesses transferred to distant posts in order to protect “the man higher up.” What faith these eminent men had in Root's character may be gathered from their conclusion:

“That the statement of Mr. Root, whether as to the origin of the war, its progress, or the methods by which it has been prosecuted, have been untrue.”

And this passage:

“What weight can his countrymen give to his (Root's) words, even in a long-considered and most important official communication? Where in the Secretary's letter is there a note of genuine manly indignation at General Smith's inhuman order? What is it but the best apology which he can make for orders that would seem black in the annals of Turkey?”

GENERAL Smith admitted that he gave the order to which these passages refer that “would seem black in the annals of Turkey.” He justified them. “He did not excuse them on the ground that his words were reckless talk, not understood as an order and not intended to be obeyed,” says the report. “On the contrary, months after the act, when on trial for an offense which shocked the moral sense of mankind, his counsel deliberately admitted that General Smith 'wanted everybody killed capable of bearing arms!'” (Page 35)

It is not necessary to go to the Thirty Years' War to find an analogy to the acts committed by the Germans in Belgium. They can be cited by the score against Elihu Root while Secretary of War under his fellow-agitator, Roosevelt. In his own letter to the President of July 12, 1902, Root quoted General Smith's order:

“I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn; the more you kill and burn, the better you will please me.”

The age limit was placed at ten years! The Manila Times of March 15, 1902, wrote as follows:

“In Several instances natives who were captured were tied to trees and submitted to a series of slow tortures that finally resulted in death, in some instances the victims living for three or four days. The treatment was the most cruel and brutal imaginable. Natives were tied to trees, and in order to make them give confessions, they were shot through the legs and left thus to suffer through the night, only to be given a repetition of the treatment the next day, in some instances the treatment lasting as long as four days before the miserable creatures were relieved by death.”

It is an officer of historic name, then serving in the Philippines, whose wife, at his request, wrote to the Philadelphia Ledger a letter which was published November 11, 1901, and in which the writer said:

“Our men have been relentless, HAVE KILLED TO EXTERMINATE MEN, WOMEN AND CHILDREN, PRISONERS AND CAPTIVES, active insurgents and suspected people, FROM LADS OF TEN UP, . . . Our soldiers have pumped salt water into men 'to make them talk', have taken prisoners of people who had held up their hands and peacefully surrendered, and, an hour later, without an atom of evidence to show that they were even insurrectos, stood them up on a bridge, and shot them down one by one to drop into the water below and float down as examples to those who found their bullet-torn corpses.”

This form of savagery Root as Secretary of War, in his official report of February 17, 1902, described in these words:

“The war in the Philippines has been conducted by the American army with scrupulous regard for the rules of civilized warfare, with careful and genuine consideration for the prisoner and the noncombatant, with self-restraint and with humanity never surpassed.”

IS it any wonder that Messrs. Adams, Schurz, Welsh, Storey, Codman and Smith should charge him with falsehoods, hypocrisy and complicity in the Philippine atrocities? “The officers in command of our forces,” these gentlemen said, “have received their orders from or through him, and have made their reports to him. Better than any other man in the United States he has been able to learn the truth about our military operations, and it has been his duty to know the exact facts.”

But what would have been the execrations heaped upon Root's head if facts like the following had come to the knowledge of the public which has not yet been so morally debased as to regard a Filipino no better than a poisonous reptile:

“Between February 1899 and August 1901 thirty privates were tried by court martial and all were convicted: There were six cases of rape, two of assault with intent to commit it, two of murdering women, two of 'wantonly killing a boy,' two of murder and five of robbery. The others were assaults and looting.”

The Germans, justified under international law for the restoration of order in an occupied country, deported some Belgians for refusing to work and forced them to work in Germany, but paying them the same wages received by German workmen—and Root compares this action to the beating down of the very pillars of civilization. But hear the statements of Mr. George Kennan, the famous explorer and author, on Root's blood guilt:

“I am not chicken-hearted, but this policy hurts us. Summary executions are, and will be, necessary in a troubled country, and I have no objections to seeing that they are carried out; but I am not used to torture. The Spanish used the torture of water throughout the islands as a means of obtaining information; but they used it sparingly and only when it appeared evident that the victim was culpable. Americans seldom do things by halves. We come here and announce our intention of freeing the people from 300 or 400 years of oppression, and say, 'We are strong and powerful and grand.' Then to resort to inquisitorial methods, and use them without discrimination, is unworthy of us and will recoil on us as a nation.” At the end of his article Mr. Kennan says:

“We find ourselves following the example of General Weyler, and resorting, if not forced to resort, to the old Spanish methods—murder, torture and reconcentration.”

AS yet Mr. Root has not charged any German soldiers with “impaling” the poor Belgians in their mad desire for destroying the “standards of civilization” as Mr. Root understands civilization. His tender heart is touched by the barbarism that makes a lot of worthless, incendiary corner loafers earn their own living; but there was no pity in his heart over the case reported by Private Andrew K. Weir, of the Fourth Cavalry, charging a lieutenant with “outrageous cruelty to a Filipino prisoner, twenty-one years old, who was stripped naked, given the water torture in the most revolting way, whipped and beaten unmercifully while he was down, kicked, strung up by the thumbs and then his ankles tied and his feet jerked from under him.” Weir charged the lieutenant with

“Cutting a strip from a man's ankle, attaching it to a piece of wood, and then coiling the flesh with the wood; with having an old man held under water until he was unconscious; with tying several times a man to a saddle horse with a few feet of slack, and then making the rider gallop, dragging the victim if he could not keep up.”

On August 27, 1901, Capt. P. W. West of the 5th Infantry, reported a mass of testimony proving that Weir's charges were true, and concluded:

“I believe that a through investigation into the matter will substantiate the charges made by Private Weir, that prisoners were treated in a cruel and harsh manner.”

The report with the evidence was sent to Secretary Root, but no action was taken; Root reported that “the war in the Philippines had been conducted with scrupulous regard for the rules of civilized warfare … with humanity never surpassed!”

Category

Historical Revisionism, The Fatherland, World War 1- 2400 reads

Comments

Not too suprised. There is

Not too suprised. There is hate for Germans way back during the first Boar War in South Africa. England took away their land which they called German West, now called Namibia. Afrikaaners had come into an agrement with the Boers sometime in the 1800's over that land. A treaty some Germans, to this day hold steadfast to.