Nuremberg hangman was a U.S. Navy-diagnosed psychopath who slowly strangled top Nazis

Sergeant John C. Woods poses for photographers in his ship’s bunk after he became a celebrity as the Army’s Hangman for the 10 alleged war criminals condemned to death by the Allies’ International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg in October 1946.

By Carolyn Yeager

This is a gruesome story – the culmination of a gruesome war which was followed up with an atrocity-filled post-war Germany occupation. Those responsible for the rampant criminality were the Allies—the All-Lies—who were successful at covering themselves with an image as world saviors.

On October 16, 1946, in a ghoulish death procession that began shortly after 1 a.m., ten political and military leaders of the Third Reich were hanged by the neck until dead by a psychopathic Navy deserter who lied about having previous experience as an executioner. He was Master Sergeant John C. Woods, promoted to that rank from private after being selected as the Army’s hangman. The promotion cannot be attributed to any merit of his own, but in order to endow him with a greater sense of worthiness for his special task. His assistant was a military policeman named Joseph Malta, a 28-year old floor-sander in private life. Both had volunteered for the job after the Army put out word for an executioner, asking if anyone had experience. Woods claimed he had hanged two men in Texas and two in Oklahoma. No records exist showing that he did.

Malta said of his work of ultimately helping to hang a total of 60 Third Reich government and military leaders, “It was a pleasure doing it.” In saying this, he echoed his colleague Woods, who was widely quoted in newspapers and magazines with these homespun words:

“I hanged those ten Nazis … and I’m proud of it … I wasn’t nervous … A fellow can’t afford to have nerves in this business.”

Woods boasted to Time magazine on Oct. 26, 1946:

“The way I look at this hanging job, somebody has to do it. I got into it kind of by accident, years ago in the States.”

He lied. The only hanging Woods had done was in the U.S. Army, where they accepted what he claimed to be his experience without any checking whatsoever. The idea of hanging others appealed to Woods, and the Army was not particular. As a person who had joined the Navy at age 18 and been diagnosed with constitutional psychopathy after going AWOL only a few months later and dishonorably discharged as “unfit to serve,” he was able to enlist in the Army in 1943 at the age of 32 and gravitate to a cushy job that very few would volunteer for.

How and why the most famous hangings of the 20th Century were botched is explained by the callous disregard of the U.S. Army headed by General Dwight David Eisenhower (an admitted German-hater) for the people and nation of Germany. The famous line “Ike” wrote to his wife Mamie in September 1944, was “God, I hate the Germans.”

We’ll start with the selection of John C. Woods as the Army’s hangman. Wood’s history is as follows:

He was born June 5, 1911, in Wichita and attended Wichita High School. He dropped out after two years and joined the U.S. Navy in 1929. After serving only a few months, he went AWOL and was dishonorably discharged with a diagnosis of psychopathic inferiority without psychosis, a term coined in Germany in the 1880s to describe irredeemable criminals who had a mix of violent and antisocial characteristics.

Woods returned to Kansas and worked intermittently as a construction laborer and part-time in a feed store in Greenwood and Woodson counties during the Great Depression. He worked for a time for the Civilian Conservation Corps but was dishonorably discharged from that after six months, according to his biographer, author French MacLean, a retired U.S. Army Colonel. Woods also worked at Boeing as a tool and die maker.

When the United States entered World War II, Woods saw it as an opportunity to improve his situation. He enlisted in the U.S. Army which he shouldn’t have been able to do since he had already been dishonorably discharged from the Navy. But the Army didn’t check his records. Prior to his induction, he had married Hazel Chilcott, a nurse; fortunately they had no children. At his Army induction, he was listed as having blue eyes, brown hair with a ruddy complexion, standing only 5’4½” tall and weighing only 130 pounds.

In 1943, he was assigned to Company B of the 37th Engineer Combat Battalion in the Fifth Engineer Special Brigade. He likely participated in the D-Day landings at Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944. Not long after, the Army put out word for an executioner, asking if anyone had experience. The Army had 96 U.S. soldiers tried with death penalty cases that were scheduled for execution in 1944, for crimes such as desertion, murder and rape while U.S. forces were in Africa and Europe. The most famous was Private Eddie Slovik, whose story was made into a television movie in 1974.

Some of those soldiers were executed by firing squad, such as Slovik. Others were hung.

Woods volunteered for the job, saying he had hanged two men in Texas and two in Oklahoma. As stated above, no records exist showing this. But on May 7, 1945, he was assigned to the Headquarters of the Normandy Base Section, but was attached back to the 2913th for duty. On September 3, 1945, Woods was released from attachment and assigned to the Headquarters CHANOR Base Section.

… his crumpled hat was always worn at an improper angle.

In October 1946, he gained world-wide fame as the official hangman for the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. He told the Stars and Stripes that Nuremberg was “just what I wanted. I wanted this job so terribly that I stayed here a bit longer, though I could have gone home earlier.”

One of his assistants, the Jew Herman Obermayer, described Woods as slovenly, unshaven, with crooked yellow teeth and dirty, unpressed pants and an insubordinate attitude. He said the hangman “defied all the rules, didn’t shine his shoes and didn’t get shaved. His dress was always sloppy.” Obermayer went on: “His dirty pants were always unpressed, his jacket looked as though he slept in it for weeks, his M/Sgt. stripes were attached to his sleeve by a single stitch of yellow thread at each corner, and his crumpled hat was always worn at an improper angle.”

This “alcoholic, ex-bum” with “foul breath, and dirty neck,” as Obermayer put it, knew he could flaunt his slovenly appearance since his superiors needed his services.

The Hangings

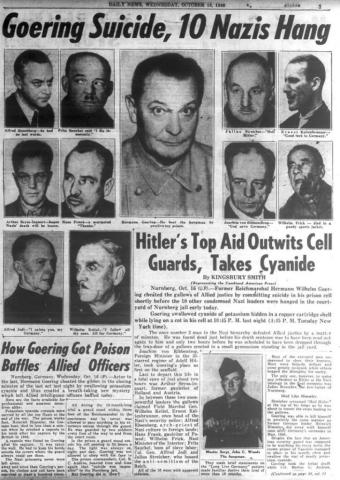

The executions took place in a brightly lighted prison gymnasium where three black wooden gallows had been erected, two for the executions and one spare. The plan was to execute one after the other, and after the first was pronounced dead and carried out, the third would be brought in to that same scaffold. After the third had fallen through the trap door, the second would be checked, pronounced dead and removed, making way for the fourth to be brought in. As you can imagine, it was a goulish scene for the witnesses. One was Kingsbury Smith who wrote a detailed report peppered with sarcastic put-downs of the Hitler regime for his newspaper, from which I took much of the following description.

The first to appear was Joachim von Ribbentrop, the Reich Foreign Minister. Time described it this way in its Oct. 28, 1946 magazine:

At 1:11 a.m. he entered the gymnasium, and all officers, official witnesses and correspondents rose to attention. Ribbentrop’s manacles were removed and he mounted the steps (there were 13) to the gallows. With the noose around his neck, he said: “My last wish … is an understanding between East and West. …” All present removed their hats. The executioner tightened the noose. A chaplain standing beside him prayed. The assistant executioner pulled the lever, the trap dropped open with a rumbling noise, and Ribbentrop’s hooded figure disappeared. The rope was suddenly taut, and swung back & forth, creaking audibly.

According to the account of Kingsbury Smith, from which these quotes are taken, Ribbentrop said in full: “God protect Germany” in German, and then added “My last wish is that Germany realize its entity and that an understanding be reached between the East and the West. I wish peace to the world.”

It took Ribbentrop 18 minutes to be pronounced dead. But two minutes after the trap door closed on the foreign minister, Field Marshall and head of the Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht, serving directly under Hitler, Wilhelm Keitel was led to the second scaffold. His last words, uttered in a full, clear voice, were translated as ‘I call on God Almighty to have mercy on the German people. More than 2 million German soldiers went to their death for the fatherland before me. I follow now my sons – all for Germany.’

In Keitel’s case the trap door, which was too small for his large frame and hindered his falling freely, opened “with a loud bang” and apparently smacked him in the face as he went down, doing extensive damage. And he wasn’t dead, his neck did not break, but he slowly strangulated as he hung hidden under the gallows, moaning and struggling. After 28 minutes he was pronounced dead. How could the U.S. Army officiate over such a travesty.

Wilhelm Keitel was a double victim of the Allies vengeful approach, because he could never have been found guilty under international law as it existed during the war. The All-Lies and their Jewish legal specialists used a NEW POST-WAR change in international law – that professional soldiers cannot escape punishment by claiming they were dutifully carrying out orders of their superiors. All during the war, the law said otherwise – that soldiers and officers were not held responsible if they were following orders. And, of course, we know that no commanding officers on the Allied side were put on trial. If they were, the Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in Europe, Eisenhower himself, would have been guilty of many war crimes.

The corpse of Wilhelm Keitel has dried blood coming out of his eyes and mouth because of his long struggle with suffocation. The right side of his face looks bloody or badly bruised and his expression is one of having endured prolonged suffering. Even in death, his body looks tense.

There was now a pause in the proceedings. The 30-odd observers were allowed to have a smoke, get up and walk around. The correspondents furiously scribbled their notes. Finally an American and a Russian doctor, both with their stethoscopes, entered the curtained portion under the first scaffold. When they emerged, they spoke to an American colonel who snapped to attention and announced to the room: “The man is dead.” The hangman, Woods, mounted the gallows and cut the rope with a large “commando-type” knife, and Ribbentrop’s limp body with the black hood still over his head was removed by stretcher carriers to the far end of the room and placed behind a black canvas curtain.

The directing colonel said to the witnesses, “Cigarettes out, please, gentlemen.” And the next condemned man was brought in while Keitel continued to hang, hidden below the gallows.

This was Ernst Kaltenbrunner, head of security. After glancing around the room, he mounted the steps with a steady gait, and his last words were: “I have loved my German people and my fatherland with a warm heart. I have done my duty by the laws of my people and I am sorry my people were led this time by men who were not soldiers and that crimes were committed of which I had no knowledge. Germany, good luck.”

Clearly, Kaltenbrunner did not have any first- or even second-hand-knowledge of “death camps” or other alleged war crimes even though he was head of the Reich Main Security Office and worked under Heinrich Himmler. But exactly because he didn’t know, his only course under Nuremberg rulings was to acknowledge their reality while asserting he had no part in them. This is what the illegal “rules of the court” forced on the defendants, and they also had no way to learn otherwise while in detention.

His trap door was sprung at 1:39 a.m. Being exceptionally tall (6’6”), and the rope said to have been not the right length for his height, he was not pronounced dead until 13 minutes later, at 1:52 a.m. But before that happened, Alfred Rosenberg was led in and went through the same process, except for being the only one to refuse his opportunity to speak any last words.

The sixth man was 69-year-old Wilhelm Frick, Minister of the Interior. He entered the execution chamber at 2:05 a.m., six minutes after Rosenberg had been pronounced dead. He seemed the least steady of any so far and stumbled on the thirteenth step of the gallows. His only words were, ‘Long live eternal Germany,’ before he was hooded and dropped through the trap. He was also badly bloodied, his corpse (below) showing the agony of his last 12 minutes of life, the time it took from the drop to his being pronounced dead.

The body of Wilhelm Frick, Reich Minister of the Interior, also shows evidence of a very difficult hanging. His face is contorted in agony and blood is everywhere. Yet he was very quiet on the gallows and only said a few words.

Post-event investigators claim that the trap door did not retain the rubber bungs when opened, so some men were hit in the face by the rebounding trap door. Others say Woods got the drop wrong … either through incompetence or on purpose. Albert Pierrepoint, the French expert hangman, has written that the correct drop is absolutely essential to ensure the neck vertebrae is severed on the “jerk,” to be certain of instantaneous death. The U.S. Army doesn’t have to answer for any of this because, as we all know, these Nazis deserved whatever they got.

Donald E. Wilkes, Jr., a professor of law at the University of Georgia Law School, noted that many of the executed Nazis fell from the gallows with insufficient force to snap their necks, resulting in a macabre, suffocating death struggle that in some cases lasted many, many minutes:

“Although [Kingsbury] Smith discreetly omitted mentioning it, the experienced Army hangman, Master Sgt. John C. Woods, botched the executions. A number of the hanged Nazis died, not quickly from a broken neck as intended, but agonizingly from slow strangulation. Ribbentrop and Sauckel each took 14 minutes to choke to death, while Keitel, whose death was the most painful, struggled for 24 minutes at the end of the rope before expiring.” https://thelede.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/01/17/the-nuremburg-hangings-not-so-smooth-either/

On Axis History Forum, we find one contributor, Max Wilson, writing:

I have one piece of research which quotes Woods as saying that he would “drop those Nazis” like poled oxen. Woods used a standard military drop of six feet for all of his victims, not the variable drops developed by the masterful British hangman, Pierrepont. Pierrepont’s technique tailored the drop to the victim’s weight, height and physical condition, almost assuring instantaneous death 100% of the time. The Nuremberg gallows also was inferior to the British design in which the double doors of the trap are caught and held open. Apparently the Nuremberg gallows allowed the doors to swing, whacking the condemned. The Nuremberg noose was a typical “cowboy” hangman’s knot, a design discarded by the British long ago and replaced by a slip-knot.

Even Reichhart, one of the master Nazi executioners, considered Woods a crude amateur and the two disliked each other intensely. Reichhart did not assist in the Nuremberg executions or the gallows design, something which has been asserted.

And another, Markus, wrote:

According to Stanley Tilles who assisted Woods at Nuremberg, he bungled the executions on purpose. In the case of Streicher. “Woods applied the hood … adjusted the noose, but placed its coils off center, [so they] would not snap Streichers neck and he would strangle. I realized instantly that this was Woods intention and I saw a small smile cross his lips as he pulled the hangmans handle.” (Tilles: By the neck until dead. Gallows of Nuremberg)

Tilles also mentions that Woods was a great german-hater. Considering that Tilles in his memoirs still does not lack sympathy for Woods, there is no reason to assume that he is not a credible witness. Third in charge was Joseph Malta. In an interview (for the [German] TV-documentation “Hitlers Helfer”) he confirmed with barely-concealed satisfaction that the hangings were badly botched and needlessly prolonged.

Julius Streicher

The seventh man to enter the gymnasium, at 2:12 a.m. was Nuremberg magazine publisher Julius Streicher, who was not a member of either the government or the military. His eyes took in the three wooden scaffolds, then moved around the room and rested on the small group of witnesses. He walked steadily to the Number One gallows, stopped at the base of the steps and uttered a loud ‘Heil Hitler!’ which echoed through the hall. An American colonel standing by the steps said sharply, ‘Ask the man his name.’ Streicher shouted, ‘You know my name well.’

At the top of the platform, Streicher proclaimed, ‘Now it goes to God.’ He was pushed to the spot directly beneath the rope, while the hangman, our friend John Woods, stood behind him holding the noose back. Streicher was swung around to face the witnesses and glared at them. Then he screamed, ‘Purim Fest 1946.’ [Purim is a Jewish holy-day commemorating the hanging of the Persian Haman and his 10 sons in ancient days, whom the Jews believed had been conspiring against them. The story is a fiction in the Book of Esther in the Old Testament. Streicher was pointing to the Jews as responsible for his execution.]

When asked if he had any last words, Streicher shouted, ‘The Bolsheviks will hang you one day.’ He then could be heard to say ‘Adele, my dear wife’ as the black hood was put over his head. The trap opened with a loud banging sound and he went down kicking. When the rope snapped taut, it continued swinging wildly and groans could be heard from within the lower interior portion of the scaffold. When they didn’t stop, the hangman Woods descended from the gallows platform, went inside through the black canvas curtain and did something that put a stop to the groans and brought the swinging rope to a standstill.

It took Julius Streicher 14 minutes to to be pronounced dead. Kingsbury Smith said everyone there was of the opinion Streicher had strangled.

Fritz Saukel, Reich Labor Chief, followed Streicher. Once on the Gallows #2 platform, he called out, “I am dying innocent. The sentence is wrong. God protect Germany and make Germany great again. Long live Germany! God protect my family.” As in the case of Streicher, there was a loud groan under the gallows as the noose snapped tightly under the weight of his body.

Colonel General Alfred Jodl, chief of Operations for the High Command, was ninth in the torture and death procession. He looked nervous but his voice was calm as he said his last words, “My greetings to you, my Germany.” A salutation or salute. What was said about Field Marshal Keitel’s immunity from prosecution applies to Jodl also. In fact, on 28 February 1953, a West German denazification court declared Jodl not guilty of breaking international law, finding that he was wrongly sentenced to death. This declaration was later revoked under pressure from the United States by a political minister in Bavaria.

Arthur von Seyss-Inquart, Czechoslovak-born governor of Austria and the Netherlands, was last. He limped on his left club-foot and the guards helped him up the stairs. In a low but intense voice, he said “I hope that this execution is the last act of the tragedy of the Second World War and that the lesson taken from this world war will be that peace and understanding should exist between peoples. I believe in Germany.”

He dropped to his death at 2:45 a.m.

No bodies were turned over to family or friends. All were cremated (burned in ovens!!) and the ashes were said to have been thrown into the Isar river.

John Woods’ own strange execution

Woods became an instantaneous international celebrity. After the hangings, he bragged: “10 men in 106 minutes, that’s fast work.”

And though he bragged he had executed as many as 347 men, in reality, says French MacLean, it was closer to 90 men.

News of Wood’s participation in the hangings came as a surprise to his wife, Hazel, who was quoted in The Kansas Emporia Gazette on Oct. 17, 1946:

“He never told me that he was doing that type of work. He didn’t mention any hangings and the first I knew of it was when I saw his picture in the papers.”

Yet, he worried there would be retribution by the Germans. He became so worried by the way the Germans looked at him, he started carrying two .45 pistols, according to GetRuralKansas.com.

Woods continued serving in the U.S. Army. On July 21, 1950, he was stationed on Eniwetok Atoll in the Pacific, a testing ground for nuclear weapons. The island was populated with German and U.S. scientists and engineers working as part of Operation Paperclip in an effort to develop the U.S. aerospace, atomic weapons and military aircraft industries.

He was standing in a pool of water, changing light bulbs, when a current of electricity suddenly coursed through the water. Woods screamed and fell back into the water, dead.

His death was a “pedestrian end,” says MacLean, for a man who once held the world stage. Woods “died faster than any of the men he executed.”

But his death may not have been an accident, MacLean thinks.

“The discussions on the internet about his death are legion. The Army ruled it an accident but the last chapter in my book is about Wood’s death. It will show the official Army report of investigation was flawed. It was wrong.”

If a German scientist or engineer working for the U.S. government carried out divine justice on John Woods it’s fine with me because he got more opportunities to indulge his psychopathic impulses than he deserved. The Army’s hangman is buried in a small cemetery in tiny Toronto, Kansas next to his wife, who died in 2000.

Category

The Third Reich- 1897 reads