Leopold Wenger's letters from France, February - July 1942

- 4114 reads

Celebrating a victory with a champagne breakfast in Caen, July 9, 1942, left to right: Schröter, Nippa and Poldi wearing his newly awarded Iron Cross 2. (Picture taken by a war reporter) Enlarge

The letters from 1942 begin with Operation Cerberus, for which Leopold "Poldi" Wenger's squadron (Jagdgeschwader 2 "Richthofen") played an essential role. This is the first of two major operations in which he was to take part in 1942, the second being the Battle of Dieppe in August. In between these two, we read of continuing dog-fights over the Channel. Poldi's first letter home was not until after Cerberus was successfully completed.

copyright 2013 Wilhelm Wenger and Carolyn Yeager

Translated from the German by Carlos Whitlock Porter

14 February 1942: Everything has been happening at once over the past few days, as you have, of course, heard from the Christmas news bulletins; and this time we are involved, too. We flew fighter support for the German fleet and were present at precisely the most exciting moments shortly before the breakthrough at the narrowest point on the Channel and in the evening air and sea battles. It was a bold undertaking and a surprise attack right in front of the Englishmen’s own front door, so to speak, with the two battleships “Gneisenau” and “Scharnhorst”, as well as with the heavy cruiser “Prinz Eugen” and many convoy ships, torpedo boats and destroyers in the front line. [Poldi is describing Operation Cerberus that I wrote about here.]

Poldi second from left on the airfield at Katwyik, Feb. 14, 1942

At Katwyik for Operation Cerberus

When German long-range guns attempted to destroy the English coastal artillery, all the houses on the square where we were trembled, and the floors vibrated at the rumbling. This day was the first time I saw aerial combat from the ground. When we started back towards the safety of the ships, we just managed it when a British destroyer attack was defeated by our ships. There was rather misty weather and the flare of the muzzle fire from the guns was getting more and more dazzling and frightening. Once we confused two ships and found ourselves suddenly being strafed by flak from one of the British destroyers. Then the Tommies tried to blow us through the heavy use of Spitfires. That failed, too. Since we absolutely had to maintain radio silence, it wasn’t possible to communicate with each other in the normal way. For example, we could only fire tracers in front of a comrade’s [plane] to let him know that he was being attacked by one or more Brits. We protected the ships in such a way that each squadron had to fly a certain sector to prevent hostile aircraft from getting anywhere near our big ships. Most of the enemy bombers were swept away from the outer ring of our fighter squadron and we seldom even saw them with all the bad weather. It was really beautiful aerial combat.

Yesterday I flew what was up until that time my northernmost flight in the maritime territory of the Friesian Islands. In the evening we were in The Hague. That is the first time you notice the difference compared with French muddling.

In Albertville I had two days off with QBI [bad weather]. Albertville is a city of ruins, in which only the church is still standing.

Icy Leuwarden airfield, Feb. 19, 1942

Photo taken by Poldi in Leuwarden, Holland 2-19-42

19 February 1942: I’m further north now, in the vicinity of Leuwarden. So much snow and ice is something new to me, it’s the first we’ve met with this winter. So I’ve quit flying in the English Channel and I‘m flying in the North Sea now. But there’s a big difference, apart from the cold. But it won’t be long until I can fly again. We all like it better here in Holland than in France; here, you can almost speak of a second Germany. (At least compared to the usual conditions in France.) Everything is clean and neat, every house is friendly, the windows are all full of flowers, now, in the winter; even relations between soldiers and the civilian population cannot be compared with France at all.

One problem, though, is the Dutch money. Nobody can make out the guilders yet. I had a couple of hours furlough today, and was able to see the city of Leuwarden during the daytime for once. Over and over again, all I could think about was the big difference between here and “La Grande Nation".

____________________________________

Sudden furlough with the family in Leoben in early March.

Poldi on holiday with his parents in Marburg, a historic city in central Germany, March 6 ...

...where they met up with Prof. Matzl.

16 March 1942: This morning about 6 o’clock I was back in Morlaix again, a whole day too early. I couldn’t know that I would have such good connections all the way through. I was already in Linz that same afternoon and waited an hour for the commuter train from Vienna, upon which I travelled through Nuremberg and Metz to Paris, where I arrived at 6:30pm yesterday, on the 15th. My stay in Paris was also very short and I was able to travel by train direct to Morlaix the same evening, where I was happy to arrive this morning. The trains were very full!

23 March 1942: My last letter was written from Morlaix. At that time, I wanted to fly to Holland, but that was impossible due to the bad weather. So I took the train by way of Paris, Brussels, Antwerp, Rotterdam and The Hague. Then I had to wait a couple of days and was finally able to fly back to my unit (Katwijk-Leuwarden). But it was still a whole week until I was back with my comrades again. This time, I travelled by train during the day, so I was able to see something new. Yesterday we were transferred again and now, after a long time, I’m back in France where I flew for the first time (according to the flight log book: Le Havre, after a relocation flight from Leuwarden to Calais and following a layover, on to Le Havre, that is, 710 km overland).

28 March 1942 : I just received the photograph of my family, taken by the photographer Fürst in Leoben during my furlough; [it was] posed just right, but the main thing is, everybody is on there!

Everything is happening at once here. Recently, we’ve been waiting for a big offensive almost any day now. All seems very normal at night now, but, at the same time, the English have had big losses. Tonight they tried to play a trick on us. You‘ve certainly heard the special reports on this. We were happy to be able to fly a few low level attacks on them, but the Tommies got hit so bad during the night that everything was all over by the early hours of the morning, around dawn.

4 April 1942: For the moment, there’s nothing really going on here (Le Havre), so it’s really the calm before the storm. But at night there’s a lot happening. The last few nights, I was able to watch the entire air attack from my window, which gives me a good view of the whole city and the entry to the harbor. Once a bomb hit the water about a hundred meters away from me, so that I was pushed gently away from the window. But the Brits score so few hits, that it’s a shame to waste so many bombs. Most of them fall in the water.

Poldi in the "readiness seat" (Sitzbereitschaft) in Le Havre

Transfer flight to Triqueville in a Me 109 on April 10

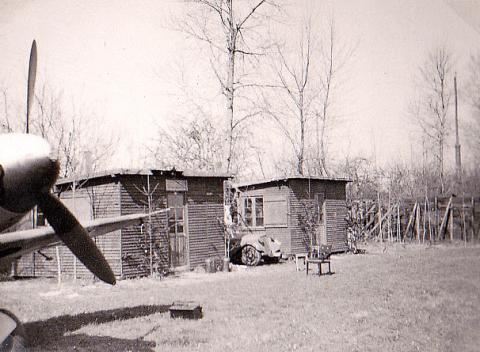

Triqueville living barracks, April 12, 1942

11 April 1942: We’ve been transferred again [Triqueville]. Although not particularly far away (40 km), there’s the usual confusion. I’m on the left bank of the Seine now, on a small square [presumably Beaumont le Roger], in the middle of the countryside. It’s a big meadow. We live in a place seven kilometers away, with about 7,000 inhabitants, in the best hotel in the region. I don’t believe we could find a bigger hotel anywhere. We’re all glad to be out of Le Havre, since the nightly bombing attacks didn’t allow us to get any sleep. On Easter Sunday night, they dropped 12 bombs on the square without damaging anything but the grass.

Now I’m sitting in a deck chair in front of my plane and “helping them wait.” None of us can understand why the Tommies no longer come over by day. Apart from the daily combat alarms, we hardly fly any more.

It’s all wonderfully green here; we have the feeling that summer is just ahead.

19 April 1942: Today I’m sitting at my command post, on duty. I was sitting here a few days ago, when there was quite a hubbub: A large of number of incoming flights and an aerial combat, with about 150 English fighter planes and bombers... and I had to sit around down here. Today, my plane is right in front of the door and there’s really nothing going on. It’s Sunday today and the Tommies aren’t flying, after all; only a few Poles and other Legionnaires.

Day before yesterday, we had some incoming flights again and, once again, no move on the part of the enemy: Spitfires were playing blind man’s bluff with us, and us with them. The cloud towers had something to do with this, since they all flew around behind them, but, on the other hand, there was no shooting. We all flew quite a bit, which was, of course, another morale booster.

25 April 1942: The English have now started yet another offensive on the Channel and came off second best for the most part. What that’s all supposed to mean is not clear. The bombs never hit their targets and are mostly simply jettisoned. But the fighter protection is very strong. Today, I couldn’t even count the number of Spitfires swarming around the bombers. They were estimated at 150 to160. Six were shot down in our sector yesterday. It was an exciting time. There were no losses on our side.

6 May 1942: It is very hot, cloudless, almost no wind. We’re sitting around in deck chairs in battle-preparedness. Strangely, it’s been completely quiet for two days. Day before yesterday, we flew two missions. We had some serious aerial combats in the morning. We chased the Tommies right back to the Isle of Wight. In the afternoon, during our second mission, there was aerial fighting all the way to the French coast. The English were more numerous than we were. There was a lot of excitement north of Fécamp and the air was full of tracers and smoke. Well, we’ll even the score next time around.

9 May 1942: For the moment, everything’s quiet around here. This doesn’t usually last more than a couple of days, though. So we can calculate fairly accurately when something is going to bust loose again. The last attack was on 6 May, that is, it will be time soon. There was a big alarm yesterday, and we all took off, but the enemy wasn’t stirring. On the 6th, though, there were big dog fights. There were about 100 to 120 English fighter planes up there. The whole sky was full of planes [Geigen]! We flew right over into the thick of it and it worked: the whole formation dissipated and the Tommies disappeared, flying away downwards away from us. Just off the English coast our squadron got into another dog fight, but the English wouldn’t really be drawn into a fight. There was wonderful weather and we had a marvellous view of both coasts from the middle of the Channel. It was so beautiful and such clear weather that I could see the Isle of Wight in great detail and the whole coast of Dover quite exactly.

One time we attacked a whole bunch of 30 Spitfires. There were only three of us, they saw us too soon, we were forced back, and our lead plane got shot down. But we got even during the next English large-scale attack: we dove right into a whole pack of them, all Spitfires, blew them up and 5 Tommies went down in flames.

21 May 1942: I’m still lying around on the same meadow as before. I was first quartered in the house of the village bank director. Now we’re in a beautiful house. There was an almighty ruckus around here in the past few days. On the 15th, we flew to Portsmouth, over Brighton and back, in the twilight, in very bad weather. We stayed there for a long time and only landed as it was getting dark... no sign of the enemy at all. The next day, our “English comrades” were kind enough to pay us a visit. There was a lot of aerial combat with a lot of Spitfires. At one point, our leader [according to the flight log book: Oberleutnant Meinberg] shot down a Spitfire in front of the whole squadron. It was something to see, the plane all aflame and the Tommy bailing out with a chute. Then our squadron flew over the Channel and we attacked an English fighter unit near Hasting. They withdrew in a hurry, though, only the last one stayed there to fight for a few moments. Our squadron leader (according to the fight log book entry Oberfeldwebel Heinzeller) shot the Spitfire down. The Tommy bailed out with his chute and landed in the water off Hasting.

To the fighter bombers:

The Red Fox emblem for the new fighter-bomber squadron

NOTE: In the early months of 1942, Hptm Frank Liesendahl (scroll down) was ordered to build a new squadron within the JG2 “Richthofen” that would go by the name 10/SG2 (Schlachtgeschwader - specialized for ground attack). In other words a new fighter-bomber squadron. This he did. Lt Nippa had the idea it should have it's own emblem representing “the red fox.” Hptm Liesendahl's new bride, a designer at the Messerschmitt airplane company, designed the fox with a ship in it's mouth (pictured above). In late May, Poldi made the change from the fighter squadron JG2 to the new squadron 10/JG2 when the aircrafts changed from the Me 109 to the new Fw 190.

25 May 1942 I’ve been transferred to another unit. It’s very beautiful here in Beaumont le Roger. Our lodgings consist of a little castle in green surroundings. Since I already know all the other people, I don’t feel like a stranger.

Poldi and Obergruppenführer Limberg on standby, June 4, 1942

13 June 1942: (Le Bourget-Paris) I’ve been travelling a lot recently. I once flew from Caen to Wevelghem and drove to Lille at night. The next day I went to Paris and back to Caen by train. I’ve been assigned to a new type of plane, the Focke Wulf Fw 190 (A-2) and after flying in, I made the ferry flight to Caen.

29 June 1942: Yesterday evening I flew my first combat flight with my new Fw 190. We did some reconnoitering flights on the English seacoast between the Isle of Insel Wight and Selsey Bill.

7 July 1942: Today I half-way participated in the sinking of a 10,000 ton submarine mother ship [the letter with the report has unfortunately been lost!]

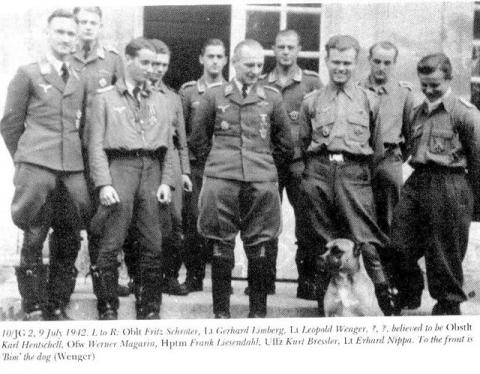

9 July 1942: Today we attacked an English convoy of ships west of Portland [Dorset]; we shot out of that convoy ships that were all together in tonage 20,000. In one attack we sank one 2,500-ton ship and severely damaged three more. I had to break off my first approach because my position was unfavorable. During a second attack I was shot at from all barrels at once and at the last moment they shot a rocket barrier right in front of my nose, so that I was still able to drop my bombs and yank my plane around. My bombs, of course, fell right next to the target. When we landed the fighter squadron leader came over; short briefing, in which, among other things, he said, “On behalf of the Führer, I award you, Lieutenant L. Wenger, the Iron Cross 2nd Class, for your decisive participation in the sinking of a 10,000 ton ship” (on 7 July 1942 in the Solent, off the Isle of Wight). Then there was a breakfast with champagne. Everybody had great fun anyway. Another formation at the same time had attacked an English airfield and hangar and destroyed a plane on the ground. We were in a really great mood. A war reporter was here, too, and took photographs. I’ll send you the pictures. [see picture at top of this page.]

12 July 1942: This afternoon I flew another mission and sank a watch ship of about 800 tons in the harbor of Brixham (Bay of Torquay) with a direct bombing hit to the starboard side of the ship. The other plane damaged a 4,000 ton freighter so severely that I must assume that it sank, too. This time, there were two of us. It wasn’t easy to approach the ship, since the harbor was full of barrage balloons and flak and very strongly protected. So we struck all at once, by surprise, out of a beautiful blue sky, flying through the barrage balloons, firing at the ships with everything we had. My ship sent up jets of flame from the superstructure after being shot at using my guns, that’s all. The bombs did the rest.

My ship capsized in half a minute, breaking in half right in the middle, while the other ship began to sink stern first. There was so much flak that we had to give up hope of being able to observe much of anything else. At any rate, I was very happy over this success, since it was the first ship I ever sank all by myself. Yesterday, my superior officer (Hauptmann F. Liesendahl) and another lieutenant also sank a destroyer in this area, that is, everybody got one. Unfortunately, the ships aren’t always where we’d like to have them.

Celebrating an air victory by Deinzer and Vock

15 July 1942: I flew my last mission on the 13th. I really wanted to attack a port. But the English coast was under clouds. So I flew towards an isolated watch ship and attacked it, with the wingman [of] my squadron. My bombs hit the ship, which was running towards the English coast at high speed, amid ships, right before the stern. My wingman’s bombs also landed right in front of the stern. Then everything happened very quickly. There was a gigantic explosion – the boilers must have blown up – and when the steam and smoke cleared away, all we could see was a trail of foam, with a whole load of ship’s parts (planks and a rubber dinghy) floating around at the end of it. There was nothing to be seen of the crew. At the same time, I got a direct machine-gun hit in the wing. The watch ship was about 800 tons and looked just like the one I sank in Brixham the day before. It all happened so fast, that I hardly had time to shoot at the superstructure when I was attacking, and what’s certain is that no more radio signals were received from the ship afterwards. This was about 5-10 kilometers southeast of Dartmouth.

A few days ago, the squadron slaughtered two pigs they had and gave a party. Everybody could eat as much as he wanted, and there was still something left over.

July 9, 1942, front row from left: Oblt Fritz Schröter, Lt Leopold Wenger, Obstlt (Lt. Col) Karl Hentschell, Hptm Frank Liesendahl (squadron leader), Lt Erhard Nippa. In front, Bim the dog. (click to enlarge) This picture appeared in a newspaper.

21 July 1942: Unfortunately, I wasn’t there during the last two missions, since I had to turn around and break off my mission due to a technical problem, and during the next to last I was on duty at the command post. That is really the most uncomfortable thing there is, just sit there and wait. Now and then you get a radio message and you look at the clock and realize that the attack must be taking place at that very moment. And then you wait for them to return and get a shock when they’re not all there.

No, I’d rather fly every mission than wait at the command post. And during this mission, our leader [Liesendahl] wasn’t there afterwards. We simply couldn’t grasp the fact that our leader was no longer with us. A few weeks ago he sank an English destroyer and now he had probably been shot down by flak. I flew my best bombing missions with him as squadron leader and learned everything from him, so to speak. He already had the German cross in gold and should have gotten the Knight’s Cross in a few days. We all hoped that he had just been captured. That wasn’t ideal, but it was better.

My suitcases are all packed again, since we’re being transferred again tomorrow. Yesterday and day before yesterday, I was still far out overland. The day before yesterday I was in Bordeaux, Vannes and Lorient. I flew from southwest France along the Atlantic coast to Caen (1170 Km.). Yesterday I arrived in Albertville and then flew to Amsterdam-Schipol and back again in the eveninng (another 1070 km).

28 July 1942: A couple of days ago, Oberleutnant Schröter asked me whether I felt like flying a mission. I’d like to see the guy that would say “no” to that. So we flew quickly to our home port and off we went, my wingman and me, with a 500 kg bomb. We had to fly some armed maritime reconnaissance in the maritime region of Start Point (east of Plymouth). We couldn’t see any ships clearly, so we flew over the land. That way we could see exactly what our bombs did to our terrestrial targets first. In the evening we flew back to our port.

- To be continued -